Why Safety Culture Matters

September 22, 2019 • Safety Culture

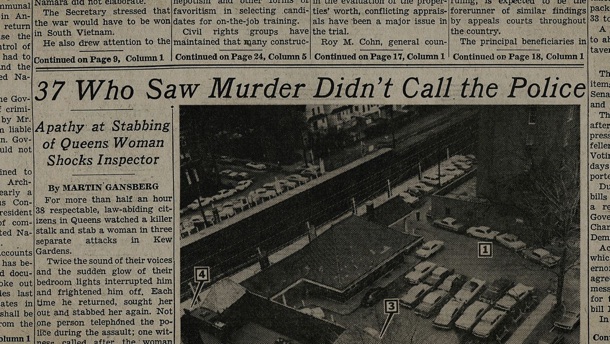

In 1964 Kitty Genovese was murdered in front of her apartment. The attack lasted 30 minutes, yet 38 nearby witnesses did nothing to help. The story sent shockwaves throughout the US. How could so many people ignore such an obvious crisis?

The initial understanding was apathy. “No one cares that someone’s life is in danger.” Or maybe, “it’s inconvenient and people don’t have the time to help”. And while that may feel true, later studies showed something new.

The Bystander Problem

An experiment at Columbia University had people take a questionnaire in a classroom setting. While they worked, the administrator waited in an adjoining room separated by a curtain. After a few minutes the administrator faked a loud, terrible injury.

When subjects were in a group, they sought to help 30% of the time. When they were alone, they helped 85% of the time.

“People were 3 times more likely to help when they were alone.”

So why don’t people respond when they are in a group? The study found that that people were afraid of over-reacting in front of their peers.

This fear was re-enforced by concerns like:

- No one else is responding, so it must not be bad

- No one else is responding, so it’s not my fault if I do nothing

- Someone else is better suited to respond. For example:

- That person is closest to the curtain, they should respond.

- I’m not a physician so I can’t help

- I don’t know the administrator, someone that knows her should help

The Fear of Over Reacting

A similar experiment had smoke come through a vent in the room. Even when their own lives were at risk, reactions were the same. In many cases, the smoke became so thick that participants coughed and fanned their faces, yet refused to acknowledge the issue for fear of over-reacting.

The “fear of over-reacting” clearly has a major impact on how people react to unsafe conditions. So how do you overcome this fear? We recommend two things:

1. Training – When workers know what issues to expect and how to handle them, they will have confidence in addressing problems.

2. Culture – When peers and supervisors are seen as safety advocates, workers will be less worried about over-reacting and more comfortable following procedures and raising concerns.

Training

Most groups have training strategies, but if you don’t then there are a lot of good options. Depending on your industry, feel free to reach out and we’d be happy to recommend a training solution for your group.

If you’re an KPA Flex client, you can actually build your own lessons within the software using PowerPoint slides, videos, quizzes, and more.

We also have a new add-on called 2020 Training. It has a pre-built lesson library including videos, slides, and quizzes that you can instantly drop in and assign to your team.

Culture

Culture is harder to pin down. How do you create a culture of safety?

GET EVERYONE INVOLVED

First off, everyone has to be involved. Many groups have top-down safety policies meaning most of the company’s “safety” happens in an isolated office. Verbose policy documents are written, sign-in sheets are filed, and stacks of reports are archived after weeks of delays.

Instead, safety should connect everyone in an organization. Employees should be on the lookout for issues. Critical field reports should notify supervisors immediately and should receive immediate feedback. Open issues should be tracked and addressed. Administrator alerts should be distributed without delay with delivery confirmation.

”Safety is everybody’s job.”

Practice

Second, practice. Observation Reports and Near Miss Reports (Behavior Based Safety) give workers the opportunity to practice their “safety” muscles by reporting safety observations. While we’re not big advocates for long-term quotas on BBS reporting, having workers submit a certain number for a short period of time can help develop good habits.

The key to good, frequent reporting is making it quick and convenient for workers to submit reports. Noting a safety issue needs to be as easy as posting to facebook. Paper forms or unnecessary questions act as hurdles that will restrict the ease of reporting.

The Kitty Genovese murder was influential in the creation of the 911 phone system. Before the 911 system, people had to lookup their local police phone number or dial the operator to be transferred. The 911 system removed all of the barriers and made it easy to report an issue.

”Make it easy to report issues.”

Feedback

Third, feedback. Many groups implement safety reporting, but few actually use the data. If a worker submits 100 reports and never hears back, it will feel like the reports are going in the trash. Feedback is critical. Employees need to know that supervisors have seen reports and take them seriously. So it’s important give occasional, positive feedback. The simple phrase “Great Catch” can stick with someone for a long time and makes it clear that they did the right thing by reporting the issue.

There are many types of feedback and each plays a role.

Direct feedback from company officials – this means a safety administrator (or any other company official) calls, texts, emails, or talks in-person with the employee about a report. Email works especially well when one official can copy in other officials to discuss and praise a good report. Digital reporting systems make this easy by simply replying to digital alerts.

Public feedback from company officials – some groups have daily or weekly meetings to discuss the project. This is a great opportunity for supervisors to highlight the best recent reports.

Peer feedback – while it may be difficult to facilitate direct peer feedback, some groups have workers nominate a safety report as a “Great Catch”. Consider giving out hats, mugs, or special PPE to the winner as an additional re-enforcement.